Dear friends,

Today we’re getting a little heady as I dive into the thoughts of critic John Berger on the difference between memories and photographs and tie this into my experience with the concept of time during the pandemic. Maybe drink some special tea while reading this one.

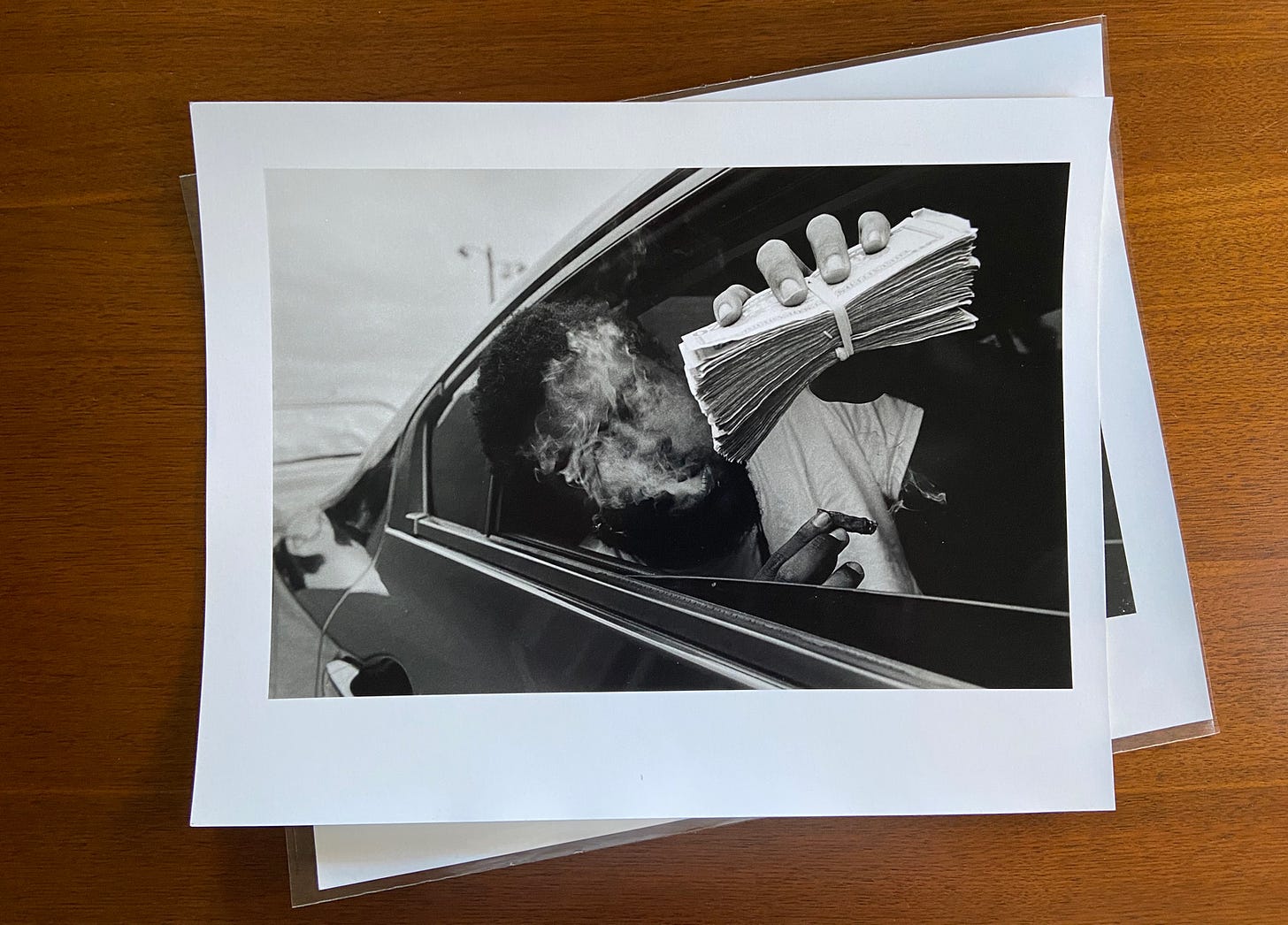

For this week’s giveaway we have gorgeous Brian Wertheim print.

Time During The Pandemic

Photography is a time-based medium. When we take a snapshot, we think of that as a moment of our life frozen so we can remember it just so. A slice of time, preserved.

My concept of time changed a lot during the months I spent in Vancouver during the pandemic. Endless weeks of groundhog days without changes to my daily routine had me forgetting whether it was Wednesday on Sunday most of the time.

Every day I’d wake up, tackle admin and email work, go for a run at 11.45am, come back to shower and eat lunch, head out for my daily Notice photo walk, come back to cook and eat, then I’d edit photos into the evening and the day would be over.

There were very few new impressions in the way I was used to pre-pandemic. No strangers to talk to and photograph in the street, no restaurant visits, no working out of coffee shops, no traveling. I walked more than 1200 km (760 miles) over the course of 123 days, but always inside of the same neighborhood.

Photographs As Memory

John Berger was an art critic whose work I find enlightening and thought provoking. I’ve been re-reading some of his work recently and it came to mind when I was sequences my upcoming Notice book.

In his essay “The Uses of Photography” Mr. Berger states that:

[…] unlike memory, photographs do not in themselves preserve meaning. They offer appearances – with all the credibility and gravity we normally lend to appearances – prised away from their meaning. […] Photographs in themselves do not narrate.

It was Mr. Berger’s opinion that photos do not have meaning, unlike our memories. In other words, any time I noticed something during my daily walks the resulting picture was simply a record of something that happened in the presence of my camera. The narration in each photograph is constructed by the set of life experiences brought to the moment by the photographer and to the image by the viewer.

In the exact moment that an image was recorded, perhaps as brief as 1/500th of a second, the physical reality and image were in harmony. In the next moment, this harmony breaks and the world changes while the image remains the same. Forever.

When you look at the photo on the right you may, based on your life experiences and childhood, see it differently from how I saw it in the moment. I may even have interpreted it differently from the way the mother and child experienced it themselves. After the photo is taken, it’s a fraction of a moment locked into an image and viewed through our own lens.

The fact that each of us can give our own meaning to a photograph is part of what makes photography so powerful. When we take an image out of context, or pair it up with another to create a new context, we craft a narrative based on our own way or seeing and our own associations and ways of seeing. From there the viewer add their own on top of that and suddenly an image can take on a whole new life.

The way the two images above connect may make it feel like they are a sequence for which I shot the second image just to the right of the first. When in fact the flowers slowly floated out of frame as the sun moved in the sky above making the shadows changed shape.

I stood in the same place for thirty minutes taking dozens of shots. In my edit, weeks later, I noticed these two fit together for a perfect diptych. My interpretation of this moment is an impression of a romantic relationship coming into existence. But you may have seen something completely different at first glance.

It’s important is to realize that looking at and interpreting an image is a powerful mechanism and it can be used for good or bad. A photograph is not a memory, but if we fail to “look at images intelligently” it can become one.

When the photos are made as purely artistic impression then we can play with this mechanism to inspire and manipulated stories into existence without much harm. If the photographs are presented as photo journalism the mechaninism can be abused to push a narrative that serves some but may not reflect the truth.

In Mr. Berger’s words:

It is because the photographs carry no certain meaning in themselves, because they are like images in the memory of a total stranger, that they lend themselves to any use. […] The camera relieves us of the burden of memory. It surveys us like God, and it surveys for us. Yet no other god has been so cynical, for the camera records in order to forget.

That’s it for this week. Some food for thought. I highly recommend setting aside some time to read John Berger’s essay “The Uses of Photography” which can be found in his book “Selected Essays” or online here.

Next week I’m trying something brand new for Process!

My pal Dave Krugman and I had a conversation about how and why we should resist the algorithm and prevent it from hijacking our creativity and output. I recorded the conversation and will include the audio alongside the written text.

In the mean time, keep shooting and take care of yourselves and others.

W

Process Giveaway!

My pal Brian Wertheim is a fantastic Los Angeles based photographer whose work is electric and human. He’s made available this beautiful print for our giveaway.

To enter email me at hello@wesley.co (please don’t reply to this note but send a separate email) before 11pm EST on December 17th and answer the following question:

Which country do you live in and which country would love to visit to photograph?

One winner will be randomly drawn and notified via email. This giveaway is for Process subscribers only. Subscribe below by clicking this button:

Make sure to show Brian some love on Instagram and check out his work.

Would you like to support Process? Great! Tell your friends about it. Just click below:

If you’re a new reader, browse the Process archives here.

Process is a weekly letter from Wesley Verhoeve.

Follow along at @wesley.